Building Resilience Against Terrorism: Canada’s Counter-terrorism Strategy

The first priority of the Government of Canada is to protect Canada and the safety and security of Canadians at home and abroad. Building Resilience Against Terrorism, Canada’s first Counter-terrorism Strategy, assesses the nature and scale of the threat, and sets out basic principles and elements that underpin the Government’s counter-terrorism activities. Together, these principles and elements serve as a means of prioritizing and evaluating the Government’s efforts against terrorism. The overarching goal of the Strategy is: to counter domestic and international terrorism in order to protect Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests.

The Terrorist Threat – 2011

Violent Islamist extremism is the leading threat to Canada’s national security. Several Islamist extremist groups have identified Canada as a legitimate target or have directly threatened our interests. In addition, violent “homegrown” Sunni Islamist extremists are posing a threat of violence. As the 1985 Air India bombing demonstrates, terrorist threats to Canada can also come from other sources. Other international terrorist groups like Hizballah or the remnants of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam continue to pose a threat, whether it is a direct attack against Canada and its allies, or the use of our territory to support terrorism globally. At home, issue-based domestic extremists may move beyond lawful protest to threaten acts of terrorism. Canadian interests around the world will continue to remain at risk of being targeted by terrorist attacks for the foreseeable future.

Addressing the Threat

Building resilience is the Strategy’s core principle. The ultimate goal is a Canada where individuals and communities are able to withstand violent extremist ideologies, and where society is resilient to a terrorist attack, if one occurs. Counter-terrorism activities are also guided by the principles of respect for human rights and the rule of law, the treatment of terrorism as a crime, proportionality and adaptability. Working through partnerships is central to the success of the Strategy. It would include collaboration with Canada’s international partners, security intelligence and federal, provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies, all levels of government and civil society. In particular, the relationship between security intelligence and law enforcement communities has strengthened over time. This seamless cooperation continues to be critical to addressing the terrorist threat.

The Strategy operates through four mutually reinforcing elements: Prevent, Detect, Deny and Respond. All Government activity is directed towards one or more of these elements.

- Prevent

Activities in this area focus on the motivations of individuals who engage in, or have the potential to engage in, terrorist activity at home and abroad. The emphasis will be on addressing the factors that may motivate individuals to engage in terrorist activities. - Detect

This element focuses on identifying terrorists, terrorist organizations and their supporters, their capabilities and the nature of their plans. This is done through investigation, intelligence operations and analysis, which can also lead to criminal prosecutions. Strong intelligence capabilities and a solid understanding of the changing threat environment is key. This involves extensive collaboration and information sharing with domestic and international partners. - Deny

Intelligence and law enforcement actions can deny terrorists the means and opportunities to pursue terrorist activities. This involves mitigating vulnerabilities and aggressively intervening in terrorist planning, including prosecuting individuals involved in terrorist related criminal activities, and making Canada and Canadian interests a more difficult target for would-be terrorists. - Respond

Terrorist attacks can and do occur. Developing Canada’s capacities to respond proportionately, rapidly and in an organized manner to terrorist activities and to mitigate their effects is another aspect of the Strategy. This element also speaks to the importance of ensuring a rapid return to ordinary life and reducing the impact and severity of terrorist activity.

Implementing the Strategy

The Strategy will serve to guide the Government’s efforts in countering terrorism. Built into the Strategy are mechanisms for monitoring the Government’s efforts and for reporting to Canadians on the Strategy’s progress, including an annual report to Canadians on the evolving threat environment.

Introduction

Canada is not immune from terrorism. A number of international and domestic extremist groups are present in Canada—some engage in terrorist activity here, or support terrorism beyond Canada’s borders. Some have worked to manipulate or coerce members of Canadian society into advancing extremist causes hostile to Canada’s peace, order and good government. Terrorism is a serious and persistent threat to the security of Canada and its citizens. Canadians expect their government to respond to threats in a manner that preserves their freedom and security.

For the first time, Building Resilience Against Terrorism clearly sets out Canada’s integrated approach to dealing with terrorist threats, both at home and abroad. It explains how Canada’s local, national and international efforts support each other to protect Canadians and Canadian interests.

The aim of the Strategy is: to counter domestic and international terrorism in order to protect Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests. By clearly articulating the Government of Canada’s approach, the Strategy:

- helps to focus and galvanize Canadian law enforcement, and the security and intelligence community around a clear strategic objective;

- provides a common basis to discuss Canada’s approach and guiding principles;

- assists in shaping future counter-terrorism priorities; and

- through periodic review, assists in regularly taking stock of the nature of the terrorist threat and how Canada is dealing with it.

Reflected throughout the Strategy is the fundamental belief that countering terrorism requires partnerships. Achieving the Government’s counter-terrorism goals will require an integrated approach not only by the Government of Canada, but by all levels of government, law enforcement agencies, the private sector and citizens, in collaboration with international partners and key allies, such as the United States (U.S.).

Partnership with citizens is important. Citizens need to be informed of the threat in an honest, straightforward manner to foster a deeper understanding of why particular actions are needed in response to the threat. Citizens also have a responsibility to act—a responsibility to work with Government and security personnel, and a responsibility to build strong and supportive local communities. Only when these tasks are shared will a truly resilient Canada be achieved.

The terrorist threat has evolved over the years, and Canada now faces ever more decentralized and diverse threats. That means Canada’s Strategy must be adaptable and forward-looking—not just to react to emerging threats but to identify and understand emerging trends.

To succeed, the Government’s counter-terrorism efforts cannot be limited to operations directed at groups or individuals already involved in terrorist activities. They must also be reinforced by preventive measures, aimed at keeping vulnerable individuals from being drawn into terrorism. These measures call for a focus on individual motivations, and other factors contributing to recruitment into terrorist activities.

It will never be possible to stop all terrorist attacks. Nevertheless, Canadians can expect that their Government will take every reasonable step to prevent individuals from turning to terrorism, to detect terrorists and their activities, to deny terrorists the means and opportunities to attack and, when attacks do occur, to respond expertly, rapidly and proportionately.

The Terrorist Threat

Terrorism is not a new tactic. In the past few decades, several hundred Canadian civilians have been killed or injured in terrorist incidents. The current iteration of al Qaida inspired terrorism is only one example of the terrorist threats facing Canada. Other nationalist, politico-religious, or multi-issue groups continue to employ terrorist tactics in support of their aims. As a result, terrorism can be seen as a tactic whose use is connected to the drivers of political violence that exist at a given time, and the existence of individuals and groups who are willing to use violence to achieve specific goals.

In Canada, the definition of terrorist activity includes an act or omission undertaken, inside or outside Canada, for a political, religious or ideological purpose that is intended to intimidate the public with respect to its security, including its economic security, or to compel a person, government or organization (whether inside or outside Canada) from doing or refraining from doing any act, and that intentionally causes one of a number of specified forms of serious harm.

Terrorism continues to pose a significant threat to Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests abroad. The global terrorist threat—from groups and individuals—is becoming more diverse and more complex. The threat to Canada from terrorism has three main components: violent Sunni Islamist extremism—both at home and abroad, other international terrorist groups, and domestic, issue-based extremism.

Sunni Islamist Extremism

Recurring instances of violence linked to Sunni Islamist extremism have punctuated the development of the terrorist threat since at least the 1970s. Today, violence driven by Sunni Islamist extremism is the leading threat to Canada’s national security. Despite having been under intense pressure for the past decade, foreign-based Sunni Islamist extremism has proven to be both adaptable and resilient. Several extremist groups have explicitly identified Canada as a legitimate target for attacks or have taken actions that threaten Canada’s international interests.

Al Qaida, led by Ayman al Zawahiri since the death of Usama bin Laden in May 2011, remains at the forefront of Sunni Islamist extremism and continues to serve as an ideology and inspiration for potential terrorists worldwide. Although al Qaida capacities have been constrained in recent years by global counter-terrorism efforts, other Sunni Islamist groups affiliated with al Qaida—either through formal allegiances or by looking to al Qaida as an example—have evolved and pose a substantial threat to Canada and the international community. The single narrative that Islam is under attack by the West survives, nothwithstanding the death of Usama bin Laden, and is shared widely by al Qaida affiliated groups.

Two of these groups in particular, al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula and al Shabaab, illustrate the diffusion of the Sunni Islamist terrorist threat. These groups and others like them may share some common cause with al Qaida, but largely remain operationally independent. The Yemen-based al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula have pursued efforts to destabilize the Arabian Peninsula, but they have also pursued international attacks that may have affected Canada, such as their failed December 2009 bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 in Canadian airspace. Al Shabaab is predominantly a threat in Somalia, but they have conducted attacks elsewhere in East Africa. Several Canadians are believed to have left Canada to join the group. These examples highlight that efforts to counter the terrorist threat to Canada must consider both al Qaida itself and the threat posed by several other different groups within the spectrum of Sunni Islamist extremism.

Radicalization of Homegrown Violent Extremists

While al Qaida affiliates may pose a threat of terrorist attacks from abroad, violent “homegrown” Sunni Islamist extremists are posing a threat of violence within Canada. Homegrown extremists are those individuals who have become radicalized by extremist ideology and who support the use of violence against their countries of residence, and sometimes birth, in order to further their goals. A number of individual extremists from Western countries have attempted terrorist attacks, inspired by, but not directly connected to, Sunni Islamist extremists abroad.

In 2006, 18 individuals were arrested in Ontario for participating in a terrorist group whose intent was to bomb a number of symbolic Canadian institutions. Of these individuals, 11 were later convicted. Another Canadian, Mohammed Momin Khawaja, was found guilty in 2008 as a result of his involvement in a failed terrorist plot in the United Kingdom. Canadians and other individuals suspected of a variety of activities related to Islamist extremism remain active across the country. Some of these individuals are spreading violent propaganda, raising money to support terrorism, helping individuals travel to foreign conflict zones, and establishing connections with likeminded extremists in Canada and abroad. Only a small number of individuals may have the intent to engage in terrorism, but homegrown extremists will pose a terrorist threat within Canada for the foreseeable future.

Like Canada, many countries have identified the challenges posed by homegrown extremism. In particular, the increased availability of Internet propaganda and sophisticated networking tools connect Sunni Islamist extremists with supporters around the world. Extremist leaders have sought to encourage homegrown extremism by using English-language material, reaching out to vulnerable individuals in Western countries and encouraging “do-it-yourself” terrorism. Radicalized Canadians have also travelled to global hot spots like Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen, training or fighting with Sunni Islamist extremist groups. These individuals could participate in terrorism abroad, return to Canada and push others to violence, or return to Canada to carry out terrorist activities on Canadian soil.

Other International Terrorist Threats

International terrorism is not a new phenomenon in Canada. The threat posed by violent Sunni Islamist extremists may be Canada’s most pressing concern, but Canada faces a broad range of international terrorist threats. It is worth recalling the tragic bombing of Air India Flight 182 in 1985—the worst terrorist attack in Canadian history—was conducted by Sikh extremists and claimed 329 lives, 280 of them Canadian.

Since some international terrorists are completely focused on conducting violence abroad, Canadian concerns are not solely limited to preventing attacks in Canada, but include the prevention of violent global extremism. Threats are also posed by Canadians who support violent conflicts abroad, or by foreigners in Canada interested in using this country for refuge, financing, recruitment or other forms of support. These threats can be further complicated when foreign states sponsor certain terrorist groups as a means of furthering their own violent objectives. Canadian interests are threatened be it a direct attack against Canada or its allies, or the use of Canada to support terrorism elsewhere in the world.

For these reasons, Canada must actively monitor the full spectrum of terrorist threats. Canada has listed under the Criminal Code more than 40 terrorist entities that are considered a threat, having either knowingly engaged in or facilitated international terrorism. These entities include the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam LTTE?, the Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA), the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT), Hamas and Hizballah.

Some international terrorist groups have more explicit Canadian connections than others. Although the civil war in Sri Lanka has ended, it is important that any surviving elements of the LTTE are not allowed to rebuild in Canada in order to engage in terrorist activities. In May 2010, for example, Prapaharan Thambithurai, an LTTE fundraiser, was convicted of terrorist financing in Canada.

Ongoing struggles in the Middle East present another example where foreign conflicts pose a threat of international terrorism. Lebanon-based Hizballah, a listed terrorist entity under the Criminal Code, has been implicated in international terrorist attacks and soliciting support from expatriate Lebanese communities around the world.

Other groups pose a threat to international and Canadian efforts to support the Middle East peace process. Hamas, for example, uses political and violent means to pursue the establishment of an Islamic Palestinian state in Israel. Hamas has been responsible for several hundred terrorist attacks and continues to present an obstacle to regional peace, despite its position as the elected government of the Gaza Strip.

Domestic Issue-based Extremism

Although not of the same scope and scale faced by other countries, low-level violence by domestic issue-based groups remains a reality in Canada. Such extremism tends to be based on grievances—real or perceived—revolving around the promotion of various causes such as animal rights, white supremacy, environmentalism and anti-capitalism. Other historical sources of Canadian domestic extremism pose less of a threat.

Although very small in number, some groups in Canada have moved beyond lawful protest to encourage, threaten and support acts of violence. As seen in Oklahoma City in 1995 and in Norway in 2011, continued vigilance is essential since it remains possible that certain groups—or even a lone individual—could choose to adopt a more violent, terrorist strategy to achieve their desired results.

Strategic Drivers Changing the Terrorist Threat

The nature of the terrorist threat facing Canada continues to diversify and become more widespread. As societies change and evolve—sometimes violently—the terrorist threat is often connected to events that are not always within Canada’s control. It remains to be seen, for instance, how events occurring across the Middle East and North Africa affect the terrorist threat.

Strategic drivers, such as globalization, rapid technological change, an increasingly networked society and fragile states, create new and different vulnerabilities that terrorists may seek to exploit. As such, governments must keep pace with a changing cyber environment, the proliferation of more sophisticated weaponry—including weapons of mass destruction, emerging telecommunication trends, and the accelerated flow of people, resources and ideas around the world.

Within Canada, terrorists may also continue exploring means to acquire financial and logistical support using both legal and illegal enterprises. A risk also remains that terrorists and their supporters will seek to take advantage of Canada’s open, democratic society, its generous legal and social networks, or exploit its advanced financial and technology sectors to redirect resources in support of their causes.

Canada’s success in remaining resilient to the terrorist threat will depend on the adoption of a flexible and forward-looking approach that effectively adapts to the changing threat environment.

Aim and Fundamental Principles

The first priority of the Government of Canada is to protect Canada and the safety of Canadians at home and abroad. That means protecting the physical security of Canadians, and their values and institutions.

The Strategy is necessarily comprehensive because the terrorist threat is multidimensional. First, Canada has been and will continue to be a target of terrorists. Second, Canadian citizens and permanent residents are known to have been involved in terrorist activities or associated with international terrorist groups. Third, terrorists may try to use Canada as a base to finance, support or conduct attacks against other countries. The Strategy is directed against terrorism in all its dimensions.

Countering terrorism demands a global strategy of partnership with others. The Strategy ensures that Canada remains a capable and reliable partner in countering international terrorism and in defending Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests.

Aim of the Strategy

The aim of Building Resilience Against Terrorism is:

To counter domestic and international terrorism in order to protect Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests

Principles Underpinning the Strategy

Principles matter. They affirm Canada’s democratic values. They provide a clear articulation of how Canada conducts its work. They explain to others around the world what Canada stands for, and what they can expect from Canada in countering the terrorist threat.

The Strategy is founded on six fundamental principles:

- Building resilience

- Terrorism is a crime and will be prosecuted

- Adherence to the rule of law

- Cooperation and partnerships

- Proportionate and measured response

- A flexible and forward-looking approach

These principles are based on fundamental Canadian values, as well as Canada’s practical experience in dealing with terrorism. The Canadian experience has been shaped by a deep attachment to democracy, the rule of law, respect for human rights and pluralism. It is based on openness to ideas and innovations, and to people from every part of the world. It is also a society that rejects intolerance and violent extremism. Security ultimately depends upon a respect for these values. When they are imperilled, the safety and prosperity of everyone will be threatened.

A proportionate and measured approach—one that has support and participation from all partners—is more likely to lead to long-term success in Canada’s overall counter-terrorism efforts, as well as in its efforts to build a resilient society.

Building resilience

Resilience is both a principle and an underlying theme of the Strategy. Building a resilient Canada involves fostering a society in which individuals and communities are able to withstand violent extremist ideologies and challenge those who espouse them. They support and participate in efforts that seek to protect Canada and Canadian interests from terrorist threats. A resilient Canada is one that is able to mitigate the impacts of a terrorist attack, ensuring a rapid return to ordinary life.

Terrorism is a crime and will be prosecuted

Terrorist activities are criminal acts. The Government will always aim to support the prosecution of those responsible for terrorist activities in Canada and abroad whenever possible, taking into account any competing national security interests that may compromise the safety and security of Canadians. Criminal investigations into terrorist activity will continue to be led by the police, supported by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and other agencies with security intelligence roles. Canada will work with foreign partners to build their legal capacity to investigate and prosecute terrorist activities and assist them in foreign prosecutions. Support for the prosecution of terrorists demonstrates the Government’s commitment to protecting the public and to countering terrorism.

Adherence to the rule of law

Canadian society is built on the rule of law as a cornerstone of peace, order and good government. It follows that all counter-terrorism activities must adhere to the rule of law. Government institutions must act within legal mandates. Authorities for counter-terrorism efforts are defined by laws consistent with Canada’s Constitution, and that include mechanisms for accountability, oversight and review that protect Canadian society from the inadvertent erosion of the very liberties that Canada is determined to uphold. Accountability develops trust, which builds security.

This principle includes respect for human rights, both those enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter) and in international legal obligations, such as international human rights and humanitarian law. Respecting and promoting human rights is fundamental to core Canadian values.

Security is also a human right. Terrorism is an attack against those very rights that are fundamental to Canadian society, such as freedom of thought, expression and association, and the right to life, liberty and security of the person.

The belief in human rights is fundamental. It governs policy choices and decision making, and it governs standards in investigations. It also guides Canada’s dealings with countries with questionable human rights records. Canadian officials will often be called upon to exercise careful judgment on these matters, but understanding the place of human rights at the core of Canada’s strategic approach provides guidance when making these decisions.

Cooperation and partnerships

The Strategy is based on the knowledge that the terrorist threat can most effectively be countered through the extensive use of cooperation and partnerships. This includes partnerships between federal departments and agencies as well as with provincial, territorial and municipal governments. Partnerships with provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies are particularly crucial. It also means engaging with industry stakeholders, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), citizens and foreign governments.

Domestically, counter-terrorism involves many federal departments and agencies (see Annex A for a full listing). Cooperation and seamless information sharing within and between security intelligence agencies and law enforcement is essential to effectively address the terrorist threat. These institutions in turn work with their provincial, territorial and municipal counterparts. One notable mechanism for doing so is through the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police Counter-terrorism and National Security Committee. Current membership includes senior officials from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), from the provincial and municipal police forces across Canada and from CSIS, as well as the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) and the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal. Governments partner extensively with the private sector and NGOs to protect the nation’s critical infrastructure and bolster the resilience of communities.

Everyone is called upon to play a part. Government partnership with citizens is critical. Citizens need to be informed of the threat in an honest, straightforward manner to foster a deeper understanding of why particular actions are needed to respond to the threat. Working in local communities, citizens will also provide the most effective avenue to strengthen society so as to maximize resistance to violent extremism. Citizens have a responsibility to work with law enforcement and security personnel. In this way, Government stands shoulder to shoulder with citizens in standing up to violent extremist ideology.

Terrorism is a global threat. Events in other countries are inextricably linked to extremism in Canada. The global environment is more interdependent than ever before, and what happens abroad can have a significant impact domestically. The dividing lines between security policy and foreign and defence policy have blurred significantly. Countering the threat demands close cooperation with other countries. This means continuing collaboration with longstanding allies and well established international organizations, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). It also means working with partners with which Canada has less history of dealing. Sometimes these efforts will be bilateral. At other times they will require working through multilateral fora, such as the United Nations (UN), the G8 and the Global Counter-terrorism Forum. It may mean working to stabilize countries that provide a permissive threat environment. Foreign policy planning is more relevant to Canada’s national security than ever before.

Canada is also an active participant in the work of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the international organization that sets standards with respect to combating money laundering and terrorist financing, and the Egmont Group, a forum for financial intelligence units around the world to facilitate and improve cooperation, especially in the area of information exchange, in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing.

Proportionate and measured response

A proportionate and measured response to terrorism is the best way to act consistently with Canadian values and to preserve community support for counter-terrorism efforts.

Canada’s approach to terrorism will be proportionate to the threat, neither an overreaction nor an underreaction. As security is a fundamental human right, the Government of Canada will uphold this right in a manner consistent with other Canadian rights and freedoms. Accordingly, the measures taken must be carefully designed to reasonably manage the actual threat while minimizing interference with the public as people go about daily activities.

A flexible and forward-looking approach

Canada’s response to terrorism must anticipate how the threat will evolve over time. Equally, Canada’s efforts will focus on prevention and address factors that make individuals susceptible to violent extremist ideologies.

Terrorist groups adapt their techniques and capabilities to their operating environment. They use new technologies, respond to international and domestic events, and create new organizational structures and capabilities in response to domestic and international counter-terrorism efforts. Canada’s approach to counter-terrorism will be flexible and forward-looking to anticipate and adapt to these changes by adjusting counter-terrorism activities and priorities.

To maximize results under the Strategy, it must also address the factors that contribute to terrorism. For this reason, the Strategy seeks to address conditions that are conducive to terrorism through efforts, such as countering violent extremism and Canada’s Counter-terrorism Capacity Building Program.

The Strategy: Prevent, Detect, Deny and Respond

This chapter describes how the Government is seeking to achieve the aim of: countering domestic and international terrorism in order to protect Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests.

Building Resilience Against Terrorism has four mutually reinforcing elements:

- prevent individuals from engaging in terrorism;

- detect the activities of individuals and organizations who may pose a terrorist threat;

- deny terrorists the means and opportunity to carry out their activities; and

- respond proportionately, rapidly and in an organized manner to terrorist activities and mitigate their effects.

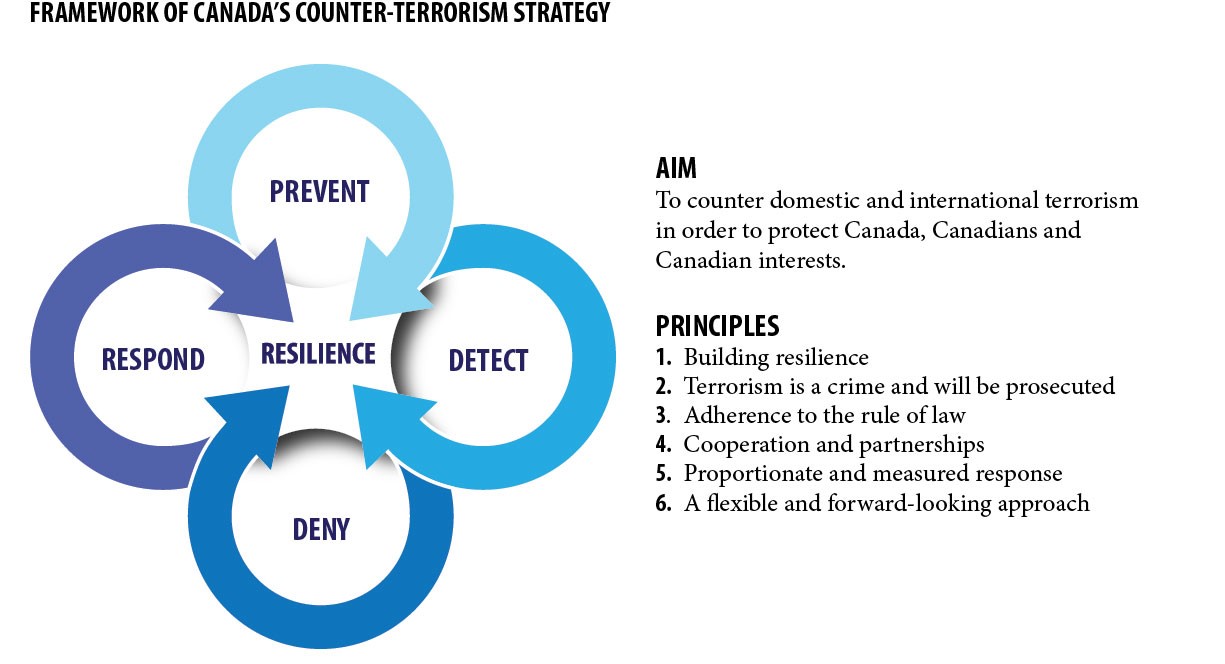

The Strategy is represented in Figure 1.

All four elements contribute to building a resilient Canada. The Prevent element fosters a Canada that is resistant to violent extremism. The Detect and Deny elements ensure Canada is able to identify terrorist activities early, and that it is a difficult target for would-be terrorists. The Respond element engenders a resilient society able to bounce back quickly when terrorist incidents do occur.

For each of the elements of the Strategy, a clear understanding of what is required to achieve success and how Canada’s efforts are coordinated and contribute to the delivery of the Strategy, is necessary. Therefore, the remainder of this chapter sets out for each element:

- the purpose of that element of the Strategy;

- the desired outcomes Canada is seeking to achieve; and

- the main programs and activities that contribute to that element.

For an issue as complex and cross cutting as counter-terrorism, many programs and activities contribute to the attainment of more than one strategic outcome, and in some cases, support more than one element of the Strategy. The programs and activities identified here are discussed in relation to the element of the Strategy to which they make their primary contribution.

Figure 1

This figure is an illustration of the aim, principles and framework of Building Resilience Against Terrorism: Canada’s Counter-terrorism Strategy.

The aim of the Strategy is to: counter domestic and international terrorism in order to protect Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests.

The Strategy is founded on six fundamental principles:

- Building resilience

- Terrorism is a crime and will be prosecuted

- Adherence to the rule of law

- Cooperation and partnerships

- Proportionate and measured response

- A flexible and forward-looking approach

The framework of the Strategy is depicted in a sphere, divided into four equal parts:

- prevent individuals from engaging in terrorism;

- detect the activities of individuals who may pose a terrorist threat;

- deny terrorists the means and opportunity to carry out their activities; and

- respond proportionately, rapidly and in an organized manner to terrorist activities and mitigate their effects.

Resilience is illustrated as a ring surrounding the sphere to demonstrate that all four elements contribute to building a Canada resilient to terrorism.

Prevent

Purpose: to prevent individuals from engaging in terrorism.

This element focuses on the motivations of individuals who engage in, or have the potential to engage in, terrorist activities at home and abroad. Canada aims to target and diminish the factors contributing to terrorism by actively engaging with individuals, communities and international partners, and through research to better understand these factors and how to counter them.

Desired outcomes

- Resilience of communities to violent extremism and radicalization is bolstered.

- Violent extremist ideology is effectively challenged by producing effective narratives to counter it.

- The risk of individuals succumbing to violent extremism and radicalization is reduced.

Programs and activities

Working with individuals and communities to counter violent extremism

The threat from violent extremism is a significant national security challenge. Radicalization, which is the precursor to violent extremism, is a process by which individuals are introduced to an overtly ideological message and belief system that encourages movement from moderate, mainstream beliefs towards extremist views. This becomes a threat to national security when individuals or groups espouse or engage in violence as a means of promoting political, ideological or religious objectives.

The Strategy articulates Canada’s commitment to addressing the factors contributing to terrorism, including radicalization leading to violence.

The threat of violent extremism does not originate from a single source, but a diverse range of groups and individuals who either actively participate in or who support violent extremist activities. For this reason, the Prevent element of the Strategy focuses primarily on building partnerships with groups and individuals in Canadian communities. Working closely with local-level partners will help foster a better understanding of preventative and intervention methods to stop the process of radicalization leading to violence.

Two examples of Prevent initiatives which seek to promote government-community collaboration include:

- the Cross-Cultural Roundtable on Security, jointly supported by Public Safety Canada and the Department of Justice, which brings together leading citizens from their respective communities with extensive experience in social and cultural issues to engage with the Government on long-term national security issues; and

- the RCMP’s National Security Community Outreach, which responds directly to the threat of radicalization leading to violent extremism through local initiatives intended to address potential political violence and to identify and address the concerns of minority communities.

To effectively counter violent extremism, a culture of openness must exist between citizens and government. This will require the Government to share knowledge with Canadians about the nature of the terrorist threat in order to foster a deeper understanding of the need for particular actions. The role of law enforcement and CSIS is pivotal. They can offer knowledge and analysis of the threat, which can assist governments and communities to develop more effective responses.

In this way, the Prevent element requires law enforcement and CSIS to develop strong capabilities in community engagement, including the enhanced language and cultural awareness skills needed to engage with diverse Canadian communities.

Other Government departments, such as Public Safety Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), CSC and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) also have supporting programs that directly or indirectly help mitigate the threat of violent extremism in Canada and abroad.

Alternative narrative

Some terrorist organizations have developed sophisticated propaganda and outreach strategies. Terrorist groups communicate with people who are potentially susceptible to violent extremist ideology through various media, especially the Internet, which has evolved as a significant forum for violent extremist communication and coordination.

The Prevent element would focus on providing positive alternative narratives that emphasize the open, diverse and inclusive nature of Canadian society and seek to foster a greater sense of Canadian identity and belonging for all. Programs would be aimed at raising the public’s awareness of the threat and at empowering individuals and communities to develop and deliver messages and viewpoints that resonate more strongly than terrorist propaganda.

Working with international partners

Under the Prevent element, Canada will continue to coordinate its efforts with like-minded countries to stabilize fragile states and limit the conditions conducive to the development of violent extremism globally. This will include the work of DFAIT, the RCMP, CSIS, the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (DND/CF) and the Canadian International Development Agency.

Under the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy (2006), member states are to address the conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism by strengthening existing programs on conflict prevention, negotiation, mediation, conciliation, peacekeeping and peace building. They also emphasize initiatives that promote inter-religious and inter-cultural tolerance, reduce marginalization and promote social inclusion. DFAIT has developed projects to work with communities to counter violent extremism in regions of concern, and to promote democratic values.

Detect

Purpose: to detect the activities of individuals and organizations who may pose a terrorist threat.

To counter the terrorist threat, knowledge is required on the terrorists themselves, their capabilities and the nature of their plans. It is also necessary to identify who supports their activities. Canada does this through investigation, intelligence operations and analysis, which can also lead to criminal prosecutions. Detection requires strong intelligence capacity and capabilities, as well as a solid understanding of the strategic drivers of the threat environment, and extensive collaboration and information sharing with domestic and international partners.

Desired outcomes

- Terrorist threats are identified in a timely fashion.

- Robust and comprehensive detection of terrorist activity and effective alerting systems are in place.

- Information is shared effectively, appropriately and proactively within Canada, with key allies and non-traditional partners.

Programs and activities

For effective detection, Canada must have strong capabilities for the collection, analysis and dissemination of usable intelligence.

Collection

The primary Government of Canada collection organizations are CSIS, the Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) and the RCMP. CSIS and the RCMP use a full range of collection methods. CSEC acquires and provides foreign signals intelligence (SIGINT) in accordance with the Government’s intelligence priorities and provides technical and operational support to law enforcement and security intelligence agencies.

Other federal organizations, such as DND/CF, DFAIT, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), Transport Canada and the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre (FINTRAC), and the Charities Directorate of the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) also collect information in support of their primary responsibilities, which is important in establishing a broader counter-terrorism intelligence picture. For these organizations the exchange of information with domestic and international partners is crucial.

The Department of Finance is currently developing options to enhance the exchange of intelligence between FINTRAC and its federal partners. FINTRAC contributes to the prevention and deterrence of terrorist financing by ensuring compliance with the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA). Millions of financial transaction reports are sent to FINTRAC each year by banks, credit unions and other financial intermediaries, resulting in financial intelligence that assists in the investigation and prosecution of money laundering, terrorist activity financing and other threats to the security of Canada. These measures strengthen Canada’s financial system by deterring individuals from using it to carry out terrorist financing or other criminal activity. To further strengthen Canada’s anti-terrorist financing regime, an Illicit Financing Advisory Committee comprised of several federal partners has been developed to identify illicit financing threats from abroad and to develop targeted measures to safeguard Canada’s financial and national security interests.

In order to detect and address risks to the charitable sector, the Charities Directorate of the CRA reviews applications and conducts audits, as well as collects and analyzes multisource intelligence. It also exchanges information with Canadian intelligence and law enforcement partners in compliance with the Income Tax Act, the Charities Registration (Security Information) Act, and the PCMLTFA.

A number of Detect initiatives promote partnership and cooperation in collection. For example, the RCMP:

- leads Integrated National Security Enforcement Teams (INSETs), based in Vancouver, Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal, which bring together federal, provincial and municipal police and intelligence resources to collect, share and analyze information in support of criminal investigations and threat assessments;

- operates a Critical Infrastructure Intelligence Team examining physical and cyber threats to critical infrastructure, which includes a Suspicious Incident Reporting system to gather information from private industry and local law enforcement about suspicious incidents; and

- operates a Counter-terrorism Information Officer initiative that provides first responders with terrorism awareness training on key indicators of terrorist activities, techniques and practices in order to help detect threats at the earliest stage possible.

Collection also occurs at the border. Through its Immigration Security Screening program, CBSA, in collaboration with CSIS, can detect the movement of potential subjects of interest as they apply for temporary or permanent residence, or refugee status. Information provided by CSIS facilitates CIC and CBSA in their efforts to assess the admissibility of these individuals under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA). CBSA also plays a role in the monitoring of cross-border currency flows, and can seize unreported currency flows suspected of being the proceeds of crime or related to terrorist financing.

Collection activities also occur outside Canada. For example, CSEC produces and disseminates foreign SIGINT to support government decision making in several areas, such as national security. CSIS conducts security intelligence collection and operations abroad in support of its mandate, and maintains strong relationships with foreign agencies with which it regularly exchanges information on potential threats to the security of Canada. DND/CF can provide strategic reconnaissance to collect or verify information in support of other government departments. Through the broad range of contacts in its overseas network, DFAIT assesses social, economic, security and political developments that help define a global threat environment. The RCMP carries out extraterritorial investigations of terrorist activity when committed against a Canadian citizen or by a Canadian citizen abroad.

Achieving the desired results under Detect requires cooperation between security intelligence agencies, and federal, provincial, territorial and municipal law enforcement. It also involves international cooperation with close allies. This includes Canada’s traditional allies, such as NATO, INTERPOL and EUROPOL, but will also involve increasing interaction with non-traditional partners Canada has less history in dealing with.

Analysis

Once information is collected, it must be analyzed to produce intelligence. Government departments and the security intelligence agencies have their own analysis and assessment units reflecting their particular responsibilities. The key organizations within the assessment community are discussed below. Other organizations provide assessments reflecting their particular responsibilities.

The Privy Council Office International Assessment Staff (PCO IAS) plays a leading role in coordinating the efforts of the Canadian assessment community and provides PCO and other senior government clients with policy-neutral assessments of foreign developments and trends that may affect Canadian interests.

DFAIT provides assessments supporting government departments concerned with international affairs as well as support to diplomatic missions, while DND/CF provide assessments on issues of concern to the defence community.

CSIS combines the information they collect themselves with information from other sources to provide intelligence assessments on terrorist threats.

FINTRAC provides strategic financial intelligence and tactical disclosures to the security and intelligence community. Financial intelligence includes analysis of trends, patterns and typologies, and provides a detailed picture of suspicious monetary movements, establishing complex links between individuals, businesses and accounts, in support of law enforcement investigations and prosecutions of terrorism related offences.

The RCMP also prepares tactical and strategic assessments in support of RCMP operations and planning, and contributes to overall Government of Canada assessment efforts through participation in PCO IAS and the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre (ITAC).

ITAC provides comprehensive and timely assessments of the terrorist threat to Canadian interests at home and abroad that integrate intelligence from across departments and agencies and from external partners. ITAC is a government resource staffed by federal representatives from a wide range of federal government institutions. Wide department and agency representation provides ITAC with strong institutional expertise, as well as access to the information holdings of their home organizations.

Dissemination

An effective approach to counter-terrorism requires that the intelligence resulting from collection and analysis activities be shared promptly with those who need it. For this reason, information sharing arrangements have been developed to disseminate threat information:

- within the Government of Canada;

- between the Government of Canada and provinces and territories;

- between the Government of Canada and specific sectors and owners of critical infrastructure; and

- with international partners.

It is important to note the role of three operations centres in this context:

- the Government Operations Centre (GOC), housed at Public Safety Canada, is a Government of Canada asset which, on behalf of the Government of Canada, supports response coordination across government and for other key national players in response to emerging or occurring events affecting the national interest;

- Marine Security Operations Centres (MSOCs) feature the co-location of five core Canadian federal partners, for the purpose of collecting and sharing information on the marine environment to create a maritime domain awareness picture; and

- DFAIT’s Operations Centre monitors world events, alerts senior governmental officials to items of national interest and supports interdepartmental task force groups. It may also become the focal point for communication with affected missions and other government departments and agencies in incidents abroad.

Internationally, Canada has well-established practices for sharing counter-terrorism information with allies, multilateral agencies like NATO and other key partners. Over time, Canada will strengthen relationships with current partners while seeking and developing new partnerships. The Strategy will serve to reinforce security initiatives between Canada and the U.S. and will complement the Canada-U.S. Beyond the Border: A Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Competitiveness.

In order to effectively detect the terrorist or terrorist financing threat, federal government departments and agencies must share information efficiently amongst themselves; with the provinces, territories and municipalities; with Canada’s allies and with non-traditional international partners; as well as with private sector stakeholders. Public Safety Canada and the Department of Justice continue to lead the development of legislative proposals to improve information sharing among departments and agencies for national security purposes that are consistent with the Charter and the Privacy Act.

The Government must leverage new technologies to ensure that information required for national security purposes is available to decision makers in a timely manner. The Government is working to upgrade this infrastructure, which provides the tools required by front line personnel and others to share classified information.

Deny

Purpose: to deny terrorists the means and opportunity to carry out their activities in order to protect Canadians and Canadian interests.

Intelligence and law enforcement actions, prosecutions, and domestic and international cooperation are important to mitigate vulnerabilities and aggressively intervene in terrorist planning. The end goal is to make Canada and Canadian interests a more difficult target for would-be terrorists.

Desired outcomes

- A strong ability to counter terrorist activities at home and abroad is maintained.

- Prosecutions are pursued and concluded effectively.

- The means and opportunity to support terrorist activities are denied.

- Strong cooperation with key allies and non-traditional partners is maintained.

Programs and activities

The Deny element of the Strategy employs a layered approach to security. It begins with programs and activities abroad aimed at denying terrorists the means and opportunities to carry out their attacks abroad and in Canada. It also includes activities at and within Canada’s borders to deny terrorists the means and opportunities to act in Canada.

The Deny element includes programs and activities:

- to deny terrorists access to capacity abroad, and to help stabilize international hot spots;

- to disrupt the movement of people and money and the acquisition of weapons, including weapons of mass destruction;

- to reduce potential security vulnerabilities in transportation networks, border protection, critical infrastructure and cyber security; and

- to investigate and prosecute individuals involved in terrorist related criminal activities.

Working internationally

Terrorism does not respect national borders. Domestic efforts to deny terrorists the means and opportunity to prepare for, and carry out, their activities must be matched by similar efforts around the world. Otherwise, terrorists will simply move their operations to a safe haven. Safe havens facilitate capacity building and attack planning. For this reason, the Deny element involves a strong degree of international cooperation.

DFAIT has the primary responsibility for coordinating Canada’s international efforts on counter-terrorism. This includes, for example, leading bilateral security consultations on counter-terrorism issues with a range of security partners.

Canada is a signatory to thirteen UN sponsored terrorism related international conventions that address threats like hostage taking, hijacking, terrorist bombings and terrorist financing, and has implemented UN Security Council Resolutions relevant to combating the financing of terrorism. Canada is involved in the development of specific legal instruments, best practices and international standards to combat terrorism, including terrorist financing, in fora that include the UN, the G7, the G8, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Organization of American States, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum, NATO, the Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe, the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, the World Customs Organization, the FATF, and the Egmont Group.

Canada also partners with the international community to promote security in other states, including fragile states, under its whole-of-government approach, which involves defence, development and diplomacy. Counter-terrorism capacity building assists other states with training, funding, equipment, technical and legal assistance to deny terrorists the means and opportunity to carry out attacks at home, and to deny them the ability to attack targets elsewhere. Through DFAIT projects and with the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering, the Charities Directorate of the CRA has contributed to capacity building initiatives in other jurisdictions to support the combatting of terrorist financing through charities.

Denying access to chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and explosives (CBRNE) weapons

This element also aims to deny terrorists access to weapons, including the CBRNE materials needed to build weapons of mass destruction. Continual adaptation of domestic policy to maintain compliance with international non-proliferation measures, such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, is necessary. This means having adequate security measures at facilities where such material is stored. It includes such activities as the role of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in regulating the importation and use of human pathogens and toxins to prevent their importation and use as biological agents by terrorists. The CBSA also plays a role in managing the movement of exports by seizing goods that are non-compliant with export laws and regulations and destined for countries that pose a threat to Canada and its allies, and by working with the RCMP to investigate and support the prosecution of individuals behind such movements.

Denying access at the border

A key element of the CBSA’s approach to combat irregular migration is its “multiple borders strategy” that strives to “push the border out” so that people posing a risk to Canada’s security and prosperity are identified as far away from the actual border as possible—ideally before a person departs their country of origin. Admissibility screening occurs prior to the arrival of an individual in Canada, or immediately after arrival, to ensure that those who are inadmissible do not enter or cannot remain in Canada. As part of its enforcement mandate, CBSA officers carry out removal orders, with security and admissibility cases given top priority. Under Beyond the Border: A Shared Vision for Perimeter and Security and Competitiveness, Canada and the U.S. are working on a number of initiatives to deny terrorists the ability to use either country as a transit point to circumvent restrictions imposed by the other.

The CBSA maintains 62 Liaison Officers in 46 locations abroad to interdict inadmissible individuals from boarding flights to Canada. The CBSA Liaison Officer network, through training, alerts and physical presence at international airports, supports transporters in the identification of improperly documented travelers. Additionally, Liaison Officers make recommendations to transporters not to carry passengers in possession of fraudulent documents or those who do not have the required travel documents to be admitted into Canada.

Managing risk away from the border through partnerships with other border administrations and industry stakeholders is a key component of Canada’s modern border management strategy. In an effort to enhance border and supply chain security to combat terrorism in the commercial stream, the CBSA has adopted several approaches including the harmonization of advanced electronic information and the enhancement of risk management systems. The CBSA also performs intelligence-based screening of commercial shipments destined for Canada. Lookouts help overseas, port of entry and inland CBSA and CIC officers identify and interdict individuals, businesses, commodities and conveyances that can harm Canada’s national security. CSIS is an active partner in this effort.

CIC has overall policy authority over entry into Canada. It is responsible for screening refugees, and admitting immigrants, foreign students, visitors and temporary workers to Canada, as well as managing the citizenship process. CIC also refuses entry to Canada to those deemed a threat to national security or public safety. Working with other federal departments and agencies, such as CSIS, RCMP and CBSA, CIC processes and screens applications, which include visa decisions, findings of inadmissibility, fraud detection, and the issuance of deportation orders.

CIC is leading the Temporary Resident Biometrics Project in partnership with the CBSA and the RCMP which will introduce the use of biometric data, such as fingerprints and photographs, in the visa issuing process to accurately verify the identity and travel documents of foreign nationals who enter Canada. This will enhance the integrity of existing immigration programs by preventing criminals from entering Canada and facilitating the processing of legitimate applicants.

Law enforcement activities

Enforcement actions by law enforcement agencies deny terrorists the means and opportunity to carry out terrorist attacks. In achieving this, cooperation among federal, provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies is critical.

For example, the RCMP-led INSETs in Ontario, Québec and British Columbia and, in all other provinces, the RCMP’s National Security Enforcement Sections (NSES), are responsible for criminal investigations involving terrorist activity. Integrated Border Enforcement Teams, comprised of both Canadian and U.S. law enforcement border agencies, and marine security initiatives, protect Canada and the U.S. from potential terrorist threats at the border and impede the trafficking and smuggling of people and contraband.

Prosecutions and other judicial measures

Federal statutes establish a legal regime that prosecutes terrorists for their activities. Thus far, investigations have led to successful criminal prosecutions by the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) for offences involving terrorist activities, such as in the cases of Mohammed Momin Khawaja, Said Namouh, and 11 members of the so-called “Toronto 18.”

As a result of these prosecutions, PPSC has developed a body of specialized expertise in terrorism prosecutions. Cases are carefully assigned to qualified prosecutors and are monitored by a National Terrorism Prosecutions Coordinator, as well as regional coordinators. Other special measures ensure that resource demands are adequately managed. Prosecution policies and specialized resource tools relating to terrorism offences are continually being refined within PPSC.

Terrorism-related cases can result in inordinately long and complex trials, typically referred to as “mega-trials.” To demonstrate the Government’s commitment to improve the efficiency of terrorism prosecutions, legislation has been passed that will streamline “mega-trials.” To support these efforts, the PPSC is also committed to developing guidelines for the prosecution of terrorism offences that reflect best practices.

Prosecuting terrorist activities may engage the relationship between intelligence and evidence, which can represent significant disclosure challenges. Individual rights, such as the right to due process, need to be balanced with the need to protect national security sources and methods. An extensive review of the disclosure process and the role of security intelligence agencies in this process is currently underway.

The Government is also committed to supporting victims of terrorism through legislation that would allow them to sue perpetrators and supporters of terrorism, in Canadian courts. This would complement existing counter-terrorism measures by deterring terrorist acts and responding to the needs of victims of terrorism.

Other judicial measures include, for example, the security certificate process under IRPA, which allows for the use of classified information in immigration proceedings before the Federal Court. The objective of this process is the removal from Canada of a non-citizen who is deemed inadmissible on security grounds.

Terrorist listing

A powerful means of denying terrorists the ability to improve their capabilities is the process of listing individuals or organizations as terrorist entities. An entity can be listed under the Criminal Code or the United Nations al Qaida and Taliban Regulations (UNAQTR) and the Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on the Suppression of Terrorism (RIUNRST).

Listing an entity is a very public means of labeling a group or individual as being associated with terrorism. Listing under the Criminal Code carries legal consequences such as making the entity’s property subject to seizure, restraint or forfeiture and includes entities not necessarily covered by the first two mechanisms. Financial institutions are subject to reporting requirements with respect to the entity’s property. It is also an offence to knowingly participate in, or contribute to, any activity of a terrorist group for the purpose of enhancing any terrorist group’s ability to carry out a terrorist activity. The UNAQTR allows for the freezing of assets of terrorist entities belonging to, or associated with, the Taliban and al Qaida. The RIUNRST involves the application of Security Council measures and allows for individual Member States to determine the listed entities. It creates a Canadian list of terrorist entities broader in scope than the UNAQTR.

Denying access to finance

Terrorism is fuelled by dollars and cents. Money provides terrorists with the weapons, training and support networks needed to facilitate their activities.

The Charities Directorate of the CRA undertakes significant compliance measures, including denial and revocation of registered charity status, to deal with applicants and registered charities that do not comply with the Income Tax Act by directly or indirectly making their resources available to support terrorist entities.

DFAIT manages the implementation of relevant UN Security Council resolutions, such as those that permit the freezing of assets. When entities (organizations and individuals) are designated under the Canadian regulations that implement UN resolutions or the Criminal Code, their assets are frozen and financial transactions with these entities are prohibited. In May 2010, Prapaharan Thambithurai, a Canadian citizen, was convicted of providing financial services to the LTTE, a listed terrorist entity, contrary to the Criminal Code.

When an entity is listed in Canada under the UN regulations, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions immediately informs Canadian financial institutions to freeze any of its assets.

The Department of Finance leads Canada’s representation in the negotiation and implementation of international standards to combat terrorist financing through bodies such as the FATF, the G7 and G20, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Critical infrastructure

The Canadian business community and other levels of government own or operate a large proportion of Canada’s critical infrastructure, which face threats from terrorists, criminals, hackers and other malicious actors. Critical infrastructure includes energy, transportation and oil and gas assets. Private companies and other levels of government are also targets for cyber terrorists, who seek to disrupt significant financial and business markets.

The Government of Canada, in partnership with the provinces, territories and critical infrastructure sectors has developed a National Strategy and Action Plan for Critical Infrastructure, which will help enhance resilience of vital assets and systems against terrorist attacks. As part of this Strategy, the Government works closely with the owners and operators of critical infrastructure to identify risks and to understand what in practice can and should be done to reduce security vulnerabilities. Extensive networks exist for communication between the Government and sectors to protect critical infrastructure.

Terrorist groups have expressed interest in developing the capabilities for computer based attacks against critical infrastructure. It can be difficult to determine the motives behind cyber attacks that perpetrate espionage or theft. The same modus operandi can be used by opportunistic criminals, corporate competitors, or foreign nation states. Terrorists use cyberspace to recruit, communicate and facilitate operations. Canada must deny them the means to operate in this domain. To this end, the Government continues to implement Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy.

Denying access to critical transportation

Transportation systems are known terrorist targets. Even unsuccessful attacks can provide publicity sought by terrorists and inflict significant economic damage. As such, the security of aviation, marine, rail, road and intermodal transportation security systems have each been improved to protect them against terrorist attacks and prevent their use as a means to attack Canada or its allies.

Terrorist groups have traditionally targeted global aviation security. The Passenger Protect Program (PPP), a shared responsibility between Public Safety Canada and Transport Canada, identifies individuals who may pose a threat to aviation security and reduces their ability to cause harm or threaten aviation by taking action, such as preventing them from boarding an aircraft. The Government remains committed to protecting the air traveling public and will continue to explore enhancements to the PPP. The Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) also plays a role in ensuring air travel remains secure by providing passenger and baggage screening that is effective, efficient, and consistent.

Security in other transportation modes such as rail and urban transit has also been enhanced in collaboration with industry and other federal and provincial government departments. Canada continues to work with international partners and organizations to establish appropriate aviation, surface and marine transportation security standards and best practices.

As the threat is dynamic and terrorists continually seek ways to exploit vulnerabilities or circumvent existing transportation security measures, the Government is committed to ensuring that Canada’s national transportation systems are secure, resilient and adaptable to mitigate emerging and potential threats.

Protecting prominent people, places and institutions

Physical security at government and public institutions, including training in terrorist identification and intervention, reduces the capacity of terrorists to strike these targets.

The RCMP provides specialist physical security for Canadian dignitaries, such as the Prime Minister and the Governor-General, Internationally Protected Persons, designated sites such as Parliament Hill and major events such as the recent 2010 Olympic Games in British Columbia and the 2010 G8/G20 summits in Ontario.

Obtaining advice from community-based security experts

The Prime Minister’s Advisory Council on National Security provides confidential advice to the Government through the National Security Advisor (NSA) to the Prime Minister on issues related to national security.

The Advisory Council is supported by PCO and meets several times a year to provide expert advice on a wide range of topics, including intelligence, law and policy, human rights and civil liberties, emergency planning and management, public health emergencies, public safety, border security, cyber security, transportation security, critical infrastructure protection and international security. The Advisory Council’s contributions are one important way in which the Government understands how better to deny terrorists the means and opportunity to attack Canada, Canadians and Canadian interests.

Respond

Purpose: to respond proportionately, rapidly and in an organized manner to terrorist activities and to mitigate their effects.

Building resilience involves strengthening Canada’s ability to manage crises, so that should a terrorist attack occur, Canada can quickly return to the routines of ordinary life. This includes supporting Canadians in need, protecting Canadian interests and minimizing the impact of terrorist activity.

Desired outcomes

- Capabilities to address a range of terrorist incidents are in place.

- Rapid response and recovery capability of critical infrastructure is maintained.

- Continuity of government and basic social institutions is ensured.

- Government leadership through effective public messaging is demonstrated.

Programs and activities

Respond programs and activities provide the capability for immediate coordinated response that will mitigate the damage of an incident, as well as longer term recovery.

The immediate response to an incident will often involve strong coordination of effort between federal departments and agencies and could also include provincial, territorial and municipal authorities, as well as private businesses, critical infrastructure owners and operators and the general public, depending on where the incident occurs and the extent of the impacts.

INSETs or NSES will lead the post-incident criminal investigation to apprehend perpetrators, prevent further related terrorist attacks and support prosecutions in the criminal courts.

Longer term recovery relies on the existence of resilient social institutions and partnerships between governments, businesses, individuals and NGOs to rebuild communities and bring those responsible to justice.

Integrated response – Incident in Canada

In practice, the immediate response to terrorist incidents, as in other emergencies, will be led by local law enforcement and emergency management authorities. This will often involve the RCMP as the first police responder in those provinces and territories where it provides local police services.

For a terrorist incident within Canada, or for incidents overseas with a domestic impact, the Government has adopted an all hazards approach to emergency management. This is articulated in the Federal Emergency Response Plan (FERP), managed by the Minister of Public Safety. The FERP is designed to integrate with other plans across all levels of government, the private sector and the community as a whole. Federal departments and agencies are responsible for developing emergency management plans for risks in their areas of accountability, consistent with guidance from Public Safety Canada. Other plans and protocols, which are annexed to the FERP, provide for responses to specific situations. Examples include the Marine Event Response Protocol and the Air Incident Protocol.

The FERP outlines circumstances, such as the need for federal support to deal with an emergency, where an integrated Government of Canada response is required. It sets out departmental roles in an emergency, governance and coordination structures and practical arrangements for providing information to government decision makers.

Particular terrorist incidents may involve specified responses from designated agencies. For example, in accordance with the National Defence Act or as an exercise of the Crown Prerogative, the CF can be called upon to support the Government of Canada’s counter-terrorism efforts and respond directly to terrorist incidents in Canada. PHAC is responsible for surveillance for diseases and events resulting from the use of CBRNE agents and coordinating a public health response to a terrorist incident. Health Canada also provides monitoring services, hazard assessments, information and advisories and decontamination strategies for CBRNE events. PHAC also maintains the National Emergency Stockpile System, which contains medical countermeasures against CBRNE agents and disaster medical supplies for use in mass casualty events.

Integrated response – Incident abroad

For a terrorist or security related incident abroad, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, supported by DFAIT, leads Canada’s response. The Canadian response to an incident will vary depending on the nature of the incident. It might include the provision of consular assistance to Canadians overseas; financial or physical aid; or deployments of experts from the federal national security community.

Major events

Ad hoc working groups plan and prepare for the security aspects of major events, such as the 2010 Winter Olympics in British Columbia and the 2010 G8/G20 summits in Ontario. These usually involve the different levels of government affected by the event, and response arrangements are tailored to the particular event in question.

In addition, Health Canada is mandated to provide services to support the overall security objectives for major international events, specifically in the areas of health and safety of federal government employees, surveillance and response to radiological nuclear threats, and support to first responders in the event of a CBRNE event or disease outbreak.

Role of Operations Centres

While Public Safety Canada and DFAIT have primary responsibility for the overall coordination of responses to domestic and international terrorist incidents, they are supported by several integrated operations centres. Government operations centres ensure effective information exchange and seamless operational integration during an incident. Depending on the type of incident, different operations centres may be more or less critical. In addition to the GOC, the DFAIT Operations Centre and MSOCs described under the Detect element, other centres of particular importance include:

- the RCMP’s National Operations Centre is a fully secure and integrated 24/7 command and control centre for centralized monitoring and coordination during critical incidents and major events;

- the CSIS Global Operations Centre (CGOC) is mandated to respond effectively and efficiently to operational and corporate queries from domestic based and foreign deployed CSIS employees, and to queries from other Government of Canada Operations Centres. It also ensures the timely and effective delivery of operational and corporate messages to and from CSIS Stations, and to and from domestic and foreign partners;

- the Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre serves as a national focal point for cyber security readiness and response, exclusive of federal government information technology and information management systems; and

- DND/CF has also established centres, such as Canada Command, to provide greater coordination with other federal departments and agencies, as well as domestic and international partners, in responding to national security events.

In addition, the Justice Emergency Team is a group of legal counsel from across government who provide coordinated legal advice and support to federal departments and agencies in emergency situations, including terrorism related incidents.

Public communications

Building resilience against terrorism requires a capacity for effective communications between the Government and Canadians in response to a terrorist event. The Government must clearly explain to the public how the incident is being managed in order to maintain public trust and confidence.

Under FERP, Public Safety Canada coordinates emergency public communications activities for the Government of Canada, between federal departments and agencies, and with other partners, including provincial and territorial governments and NGOs. DFAIT is responsible for communicating with foreign states and organizations and is also the lead for public communications on behalf of the Government of Canada with respect to incidents abroad.

Way Forward

Terrorism will remain a dominant feature of the national security landscape for the foreseeable future. As counter-terrorism involves many departments and agencies, implementing the Strategy will require an integrated approach across the Government of Canada. The Strategy will only succeed with effective partnerships. These include partnerships with the provinces and territories, law enforcement agencies, international organizations, other countries, the private sector, NGOs and the broader community. Therefore, a crucial element of the Government of Canada’s implementation approach across all elements of the Strategy will be forging strong, effective and mutually supportive relationships in counter-terrorism, with activities and responsibilities shared where appropriate between those partners.

Delivery of Programs and Activities

Ministers, departments and agencies are committed to maintaining strong policy and program design capabilities.